The objective of any feedlot is to ensure maximum efficiency in the shortest possible time, with the best profitability. For this reason, biosecurity management upon the arrival of cattle plays a fundamental role in ensuring their health and good performance throughout their stay in the feedlot facilities, guaranteeing productivity and safety in the meat production chain.

Standardization and acclimation

In the feedlot system, the cattle batch is managed upon arrival and remains in the facilities until slaughter. The origin of the cattle can vary, from those raised on the farm itself (home-bred) to those purchased from third parties. These, in turn, can be purchased at weaning (subject to standardization during the rearing period) or at a more advanced age (yearling/lean steer), coming from various origins.

One of the first points to consider is the transportation of cattle to the feedlot. In addition to dehydration, stress leads to the release of chemical mediators that can cause a decrease in the immune response, making it crucial to provide an adequate reception environment to minimize this impact.

The mixing of cattle from different places complicates the standardization of the herd’s health history, in addition to increasing exposure to infectious agents, a predisposing factor for the development of diseases.

Upon cattle entry, there is an opportunity to homogenize the lots. Thus, it becomes essential to adopt customized protocols that consider the origin of the acquired cattle and the specific characteristics of each lot.

Triad: clostridial diseases, parasitic diseases, and respiratory diseases

Bovine Respiratory Disease (BRD) complex continues to be registered as the leading problem concerning the health of confined cattle.

Parasitic diseases also represent a concern, especially in lots with an uncertain health history. In addition to problems with fractures, accidents, and nutrition-related issues, clostridial diseases rank among the main ailments affecting confined herds.

According to the survey conducted by Confina Brasil in 2023, more than 80% of the interviewed feedlots implement a basic entry protocol, including cattle deworming, clostridial disease prevention, and the administration of respiratory vaccines.

The first dose of vaccination against clostridial diseases and the main respiratory diseases should be administered approximately 30 days before entry into the feedlot, followed by a booster on D0 (day of feedlot entry). Furthermore, protection against ectoparasites is recommended upon the arrival of the cattle, as tick infestations can result in delays in weight gain and productive losses.

Prevention: better than a cure?

In feedlot operations, any problem that interferes with the good performance of the cattle can have a significant impact on the operation’s profitability.

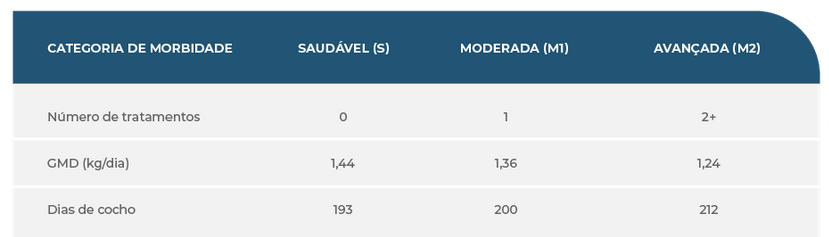

The economic impacts of inefficient biosecurity management have been studied for decades. A study conducted by Bateman et al. (1990) observed that cattle affected by pneumonia during the feedlot period lost 14 kilograms compared to those not affected by the disease. Similarly, Smith (1996) monitored a feedlot for 28 days and identified a 23-kilogram decrease in weight gain for sick cattle compared to healthy cattle. More recently (2007), Waggoner et al. evaluated the impact of feedlot morbidity on average daily gain (ADG) and carcass characteristics. For better visualization, the results are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1 | Impact of feedlot morbidity on ADG and carcass characteristics.

Source: Waggoner, J.W et al., 2007 / Adapted by Scot Consultoria

Steers considered healthy (S) achieved an ADG of 1.44 kg, while cattle with a moderate level of morbidity (M1), who received up to one veterinary treatment, recorded an ADG of 1.36 kg. On the other hand, cattle with advanced morbidity (M2), who required up to 2 treatments during the feedlot period, showed an ADG of 1.24 kg. There was also an increase in the number of days the animals remained on feed, with the following results: 193 days for group S, 200 days for group M1, and 212 days for group M2.

Therefore, in addition to a drop in productivity and the prolonged stay of sick cattle, morbidity rates are strongly associated with treatment costs and economic losses resulting from cattle mortality.

Health rounds

These “health rounds” are inspections carried out in feedlot pens, with the aim of evaluating the batch and early identification of health problems, allowing necessary measures to be taken to prevent or treat diseases during the cattle’s stay in the feedlot.

The two-to-three-week period following the introduction of cattle into the feedlot marks the most challenging period. For this reason, animal monitoring should be more frequent.

Cattle are confined, on average, for 90 to 100 days. The frequency of these inspections can vary throughout the feedlot cycle. These inspections are more rigorous during the first three weeks, with up to two daily rounds recommended during this phase. After this initial period, the frequency is reduced to one inspection per day, maintained for approximately six weeks, totaling about 40 days.

After the 40th day, it is possible to conduct intermittent inspections (every other day); however, in case of a disease outbreak, it is crucial to resume daily inspection frequency.

During the rounds, it is important that the sweep is carried out uniformly throughout the pen, always encouraging the cattle to move.

Conclusion

Considering the significant impact of morbidity on cattle performance during the feedlot period, it is crucial to emphasize that biosecurity expenses represent less than 1% of the total costs of this process, as pointed out by Martins (Martins, R.A, 2016). Therefore, neglecting herd vaccination or parasite control is not justifiable, as these practices result in significant productive losses that directly compromise the system’s profitability.

The entry management of cattle into the feedlot is essential and requires an adapted approach, taking into account the specific characteristics of each property. By implementing adequate biosecurity protocols, it is possible to ensure not only the well-being but also the productive performance of the herd, avoiding losses during this stage and contributing to the operation’s profitability.